Designing Freedom – 1

How to Design Organisations that Enhance Freedom, rather than Suppressing it

This is the first of two posts about Designing Freedom.

The second post is here.

In November 1973, Stafford Beer presented the annual Massey Lectures broadcast on Canadian Broadcasting Corporation radio, in the form of six half-hour talks, one broadcast every night for a week, which you can listen to here.

Since 1961, the Massey Lectures have been Canada’s Premier Public Intellectual Forum, with the most distinguished figures talking about the most important topics of the day. Those figures have included J K Galbraith, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr, R. D. Laing, Claude Lévi-Strauss, Jane Jacobs, Willy Brandt, Doris Lessing, Noam Chomsky and Margaret Atwood. It was therefore a great honour and a sign of his high social status, when Beer was invited to present these talks.

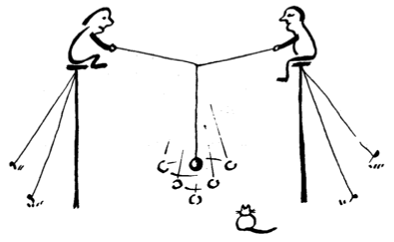

Beer’s lectures were published as this book with the same title as the Lectures, with notes at the end of each chapter, illustrated with his own drawings.

I will now summarise the first three talks:

I The Real Threat to “All We Hold Most Dear”

The little house where I have come to live alone for a few weeks sits on the edge of a steep hill in a quiet village on the western coast of Chile. Huge majestic waves roll into the bay and crash magnificently over the rocks, sparkling white against the green sea under a winter sun. It is for me a time of peace, a time to clear the head, a time to treasure.

The opening paragraph

Beer starts by comparing human institutions to the waves crashing over the rocks – they are examples of “dynamic systems”, not “things”. The waves hitting the rocks are dynamic systems collapsing and he is concerned that the institutions we are so proud of are, too. His evidence for this was increasing concern about global economic inequality, once-proud cities rotting from the centre, increasing environmental pollution, planetary limits to economic growth and a general sense that institutions were not capable of responding fast enough to unfolding events.

There was a sense that, from families to larger scale communal groups, social solidarity was disintegrating. Beer says that some people thought the solution was to double-down on traditional values – enforce the old values. But he was convinced that this would not work. He believed that the signs of crisis were outputs generated by the way the institutions were organised – rather than unfortunate side-effects of their operation.

He talks about how systems maintain their existence by complex feedback loops that maintain a stable state. But any system that gets perturbed has a finite relaxation time – the time it takes to settle down after each perturbation. If it keeps receiving perturbations faster that its relaxation time, it will become unstable, become unable to learn, and eventually collapse – unless it can be re-designed to cope.

Beer thinks that our institutions are going unstable because they were designed for a slower world, but he was optimistic that they could be successfully re-designed. However, if they were not re-designed, they would respond by reducing our variety to make it fit inside their expectations. In other words, they would increasingly deprive us of our freedom.

Our own dysfunctional institutions are the real threat to all that we hold most dear.

You can listen to this half-hour lecture here.

II The Disregarded Tools of Modern Man

The observed fact is that the culture takes a long, long time to learn. The observed fact also is that individuals are highly resistant to changing the picture of the world that their culture projects to them.

I am trying to display the problem that we face in thinking about institutions. The culture does not accept that it is possible to make general scientific statements about them. Therefore it is extremely difficult for individuals, however well intentioned, to admit that there are laws (let’s call them) that govern institutional behaviour, regardless of the institution.

….

The consequences are bizarre. Our institutions are failing because they are disobeying laws of effective organization which their administrators do not know about, to which indeed their cultural mind is closed, because they contend that there exists and can exist no science competent to discover those laws. Therefore they remain satisfied with a bunch of organizational precepts which are equivalent to the precept in physics that base metal can be transmuted into gold by incantation—and with much the same effect. Therefore they also look at the tools which might well be used to make the institutions work properly in a completely wrong light. The main tools I have in mind are the electronic computer, telecommunications, and the techniques of cybernetics….

….

I am proposing simply that society should use its tools to redesign its institutions, and to operate those institutions quite differently. You can imagine all the problems. But the first and gravest problem is in the mind, screwed down by all those cultural constraints. You will not need a lot of learning to understand what I am saying; what you will need is intellectual freedom. It is a free gift for all who have the courage to accept it. Remember: our culture teaches us not intellectual courage, but intellectual conformity.

Having talked through the difficulties, Beer embarks on explaining the fundamentals of cybernetics with great clarity.

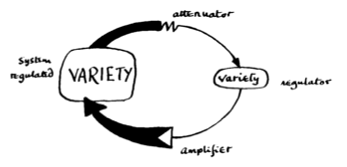

He already introduced, in Talk I, the concept of variety – the number of states a system can get into. Even simple systems have mathematically vast variety, but that can be managed as long as it is matched by the variety of whatever is regulating that system. This is known as Ashby’s Law of Requisite Variety – the fundamental law of cybernetics.

On the consumer side, we put on the advertising pressure to pretend that full account is taken of the customer’s variety—which is impossible. On the electoral side, we lose the freedoms we have, when our variety is attenuated, because we are not asked how the attenuation should be done. No politician would dare to ask his electorate that question, because he is too busy standing for the inalienable rights which it is perfectly obvious we have not in any case got. Nor can we have them: let’s look the facts in the face.

Beer explains Ashby’s Law with reference to how a Department Store manages the variety of demands made by customers. Then he has a bit of a rant about how the three tools the electronic computer, telecommunications, and the techniques of cybernetics were being misused and making things worse, then calms down and promises to use the next three lectures to consider constructive policies for handling variety.

What I have been calling a pattern is what a scientist calls a model. A model is not a load of mathematics, as some people think; nor is it some unrealizable ideal, as others believe. It is simply an account – expressed as you will – of the actual organization of a real system. Without a model of the system to be regulated, you cannot have a regulator. That’s the point.

You can listen to this half-hour lecture here.

III A Liberty Machine in Prototype

In particular, I have expressed the view that the whole business of government, that gargantuan institution, is a kind of machine meant to operate the country in the interests of individual freedom. But, for just the kinds of reason examined in the first two lectures, it does not work very well—so that freedom is in question to a greater or lesser extent in every country of the world. So, I declared, let us redesign this “liberty machine” to be, not an entity characterized by more or less constraint, but a dynamic viable system that has liberty as its output.

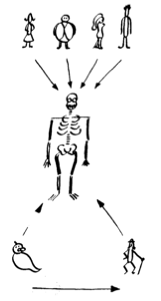

In this talk, Beer articulates a vision of how to manage government by building a real-time control system. His model for thinking about this is based on how the real-time control system of the human being works. It manages the huge variety coming from the environment and from inside itself by breaking things down into different levels of recursion, then applying the same principles of control at every level.

In the human body, examples of these levels of recursion, working down the scale, might be:

Organs, such as lungs, heart, kidneys, liver, digestive system

Cells of each type within these organs

The control systems that knit these together are the nervous system, bloodstream and hormones flowing through it.

In a nation state, examples of these levels of recursion, working down the scale, might be:

Industries

Enterprises within those industries

The control systems that knit these together are messaging services, flows of materials and money.

Beer envisages Control Rooms with real-time displays at each level.

The secret of how to manage the variety is that, at each level, messages that indicate normality are simply filtered out – attention only needs to be paid to abnormal patterns.

This is how biological systems, such as our own bodies, work, and Beer reveals that he had spent the last two years devising such a real-time system for the Chilean economy, under the regime of President Salvador Allende.

He had got far enough into this to be confident of what he was describing. The hardest part of the job was devising clever software to manage the filtration of variety and the presentation of the information in an intuitive manner in the Control Rooms. Once the software has been developed, it can operate in exactly the same way at every level of recursion, so there is no need to develop different software for different domains that need governing.

Then we can see what our potential model of the whole economy looks like. It consists of a dynamic system of simple models of dynamic systems, fitting into each other like Chinese boxes. Each box is called a level of recursion, because what we are doing is to reduplicate a cybernetic system of regulation recursively, that is over and over again, using the same components with appropriate variety adjustments. The law of requisite variety has to be satisfied at each level of recursion so that stability is induced, and off we go. Information continuously passes up and down this recursive system, appearing in its right form in the control room of the level concerned.

He envisaged decision-making and scenario planning as so intuitive that it was possible for all parties involved to participate, thus dissolving the class distinctions between workers and managers, members of the public and bureaucrats.

Unfortunately, his work in Chile had been violently brought to an end by the military coup led by Augusto Pinochet on 11th September 1973, the death of Salvador Allende and the “disappearance” of thousands of people, including many of his friends and colleagues.

So I move to the fourth and final point for today. Individual freedom has been lost, momentarily at least, in Chile. I think I know how; but it was certainly not because the people became victims of technocracy. What is clear is that everything that I have described was accomplished (and ended) in two years, and it was not fast enough. When I drafted these lectures, and outlined the hypothesis you heard—that perhaps our institutions could not react fast enough to avoid catastrophic collapse—I remember thinking that I should have to defend myself against a charge of sounding a premature and too scare-mongering an alarm. Do you care to make that allegation now?

The final paragraph

You can listen to this half-hour lecture here.

Stay tuned for the second and final instalment of Designing Freedom….